Will “AI” replace venture capital?

Those who come are welcome, those who leave are not regretted. Episode#27

If I had a talent for mathematics and could write code, my life would have undoubtedly been different.

Around 2000, I wrote a little HTML, but I thought it wasn't for me and quickly gave up. However, even someone like me could ride on the dot-com bubble wave and co-founded startups like WebCrew (listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange Mothers in September 2004) and Interscope (sold to Yahoo! Japan in 2007).

Now that AI dominates the world, it's probably a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for those who can program. It's reminiscent of the dot-com bubble around 2000.

Although I can't program, my life changed significantly when I became involved with SunBridge in March 2011. Since the Internet bubble, I have been a person in which VCs have invested, but when I joined SunBridge, I sat at the other side of the table to invest in startups.

I appreciate Allen Miner inviting me to SunBridge with his words, "Unless it's something extraordinary, I won't refuse what Hiraishi-san wishes to pursue!"

As those of my generation involved in internet-related startups and venture capital know, he was the first representative of Oracle Japan. Fluent in Japanese, he was sent to Japan during his Oracle days when founder Larry Ellison told him, "Go and establish the Japanese market!"

SunBridge is a unique company founded by 6-7 OBs of Oracle US and Oracle Japan, including Allen. Though commonplace now, back in 2000, they rented an entire floor (I believe it was the 17th floor) of Shibuya Mark City, which is still one of the landmarks in Tokyo, and operated a co-working space. A very innovative NPO was also a tenant there, making it what we would now call a "diversified" space.

Allen was a colleague of Salesforce's Marc Benioff at Oracle USA. When Marc started Salesforce, he told Allen, "Japan will undoubtedly become a large market for cloud computing, so I want you to handle Japan."

However, Allen had just launched Sunbridge with his former Oracle colleagues, so he couldn't accept the offer. Instead, Kitamura-san, a founding member of Sunbridge, established Salesforce's Japanese subsidiary. Sunbridge and Salesforce USA invested in it, and Salesforce Japan started as a joint venture. Ten years later, when Marc Benioff wanted to make the highly successful Salesforce Japan a 100% subsidiary, Sunbridge realized a capital gain of "over US$100 million.

Using this as a foundation, Allen, who had returned to Silicon Valley due to certain circumstances, returned to Japan to restart a co-working space, startup investments, and acceleration programs. However, while his old companions gathered around him, young entrepreneurs and startups of that time didn't, as he was in a "Rip Van Winkle" state.

That's natural since he had been away from Japan for a while.

Then, he happened to meet me again after two and a half years and asked, "Would you like to work together?"

I recently met with Allen about a particular matter for the first time in a while. Although I wasn't expecting it, Allen agreed to invest in my new company! Yeah!!!

I apologize. Before getting to the main topic, there's one more thing I want to share.

Through participating in Sunbridge, I met Keith Teare, essentially TechCrunch's co-founder. I say "essentially" because TechCrunch was a startup born from Archimedes Labs, a startup studio he ran. While he was a shareholder, he wasn't involved in its operations.

Although Keith is hardly known in Japan, he's a prominent figure in Silicon Valley's tech industry whom everyone knows. He moved from the UK to Silicon Valley, and when he first received investment from a venture capital firm (DFJ), he was in the same round as Elon Musk. He has worked with Microsoft and Google and has firsthand experience of Silicon Valley's evolution.

Keith has also agreed to invest in my new company and become an advisor.

He runs a startup called SignalRank that develops an algorithm to analyze which Series B startup will become the next Unicorn. This algorithm predicts the probability of Series B and later startups becoming unicorns and aims to "index" them (like the S&P 500, etc.). It's an extraordinarily ambitious and innovative business.

His startup's investors include notable figures such as Tim Draper (who was the capitalist in charge when DFJ invested in him) and Garry Tan (current Y-Combinator CEO).

Now, let's get down to the main topic. The information I want to introduce is from Keith’s Newsletter, That Was The Week. If you are interested, you should visit his Substack page. But let me introduce what captured my attention.

A database called “crunchbase” started as a spin-off from TechCrunch. As most of you know, it covers the founders of startups worldwide, their fundraising status, business status, etc.

The current CEO of crunchbase, Jager McConnell, made a public announcement saying, “Historical Data is Dead.”

Today, we’re relaunching Crunchbase as an AI-powered, predictive company intelligence solution. We’re moving beyond historical data, showing people not just what happened to a company yesterday or today, but what will happen to that company tomorrow. by Jager McConnell, CEO at crunchbase

So, what impact will these changes brought about by AI have on the venture capital industry?

That is the subject of this entry.

Keith founded and runs SignalRank, which collects data on various events leading up to Series B (e.g., the backgrounds of the founding members, where they are raising funds, etc.) and analyzes the differences between startups that have reached Series B and those that have not.

So, why Series B and beyond?

The answer is that up until Series A, the elements are firmly "personal" and not patterned enough to allow for statistical analysis, making it extremely difficult to find any "regularities" in them.

I wrote "personalized” to mean that scientific analysis is ineffective when investing in seed and early-stage startups, and decisions are primarily based on the "intuition" of angel investors and venture capitalists.

When I managed Sunbridge Global Ventures, we had to be accountable to our LPs (Limited Partners: fund investors). Although we discussed investments in the investment committee, there were no quantifiable elements to verify. Decisions were made based on discussions centered around the perspectives of the investment committee members, including myself.

Furthermore, I have never thoroughly examined a business plan when I invest personally as an angel investor. Anyone with a decent mind can write a beautiful business plan, but it's almost 100% certain that things won't go according to plan, and it's safe to say that there are no startups that don't “pivot.”

At the seed and early stages, the only point of judgment is the quality of the founders and founding members. It's closer to investing in the founders and founding team rather than investing in the business plan or its model.

So, what happens from Series B onwards? It will likely become a competition of algorithms. Let's consider this using the example of SignalRank, managed by Keith.

The SignalRnk algorithm evaluates 93% of Series B candidates as “NO (unsuitable for investment).” According to the algorithm, 87% of startups that SignalRank judges as “NO” fail.

Their definition of “success” is “a valuation increase of at least five times within five years of Series B.”

Predicting success is excellent, but predicting the probability of failure is also very useful.

So, what about the 7% of startups the algorithm says are “yes”?

31% of these will achieve the “success” they define. In other words, 1/3 of the Series B rounds that SignalRank “recommends” will grow to a valuation of more than 6 times within 5 years.

So, what is the success rate for general venture capital investment?

The answer is that it is extremely rare for 30% (3 out of 10 companies) to be successful.

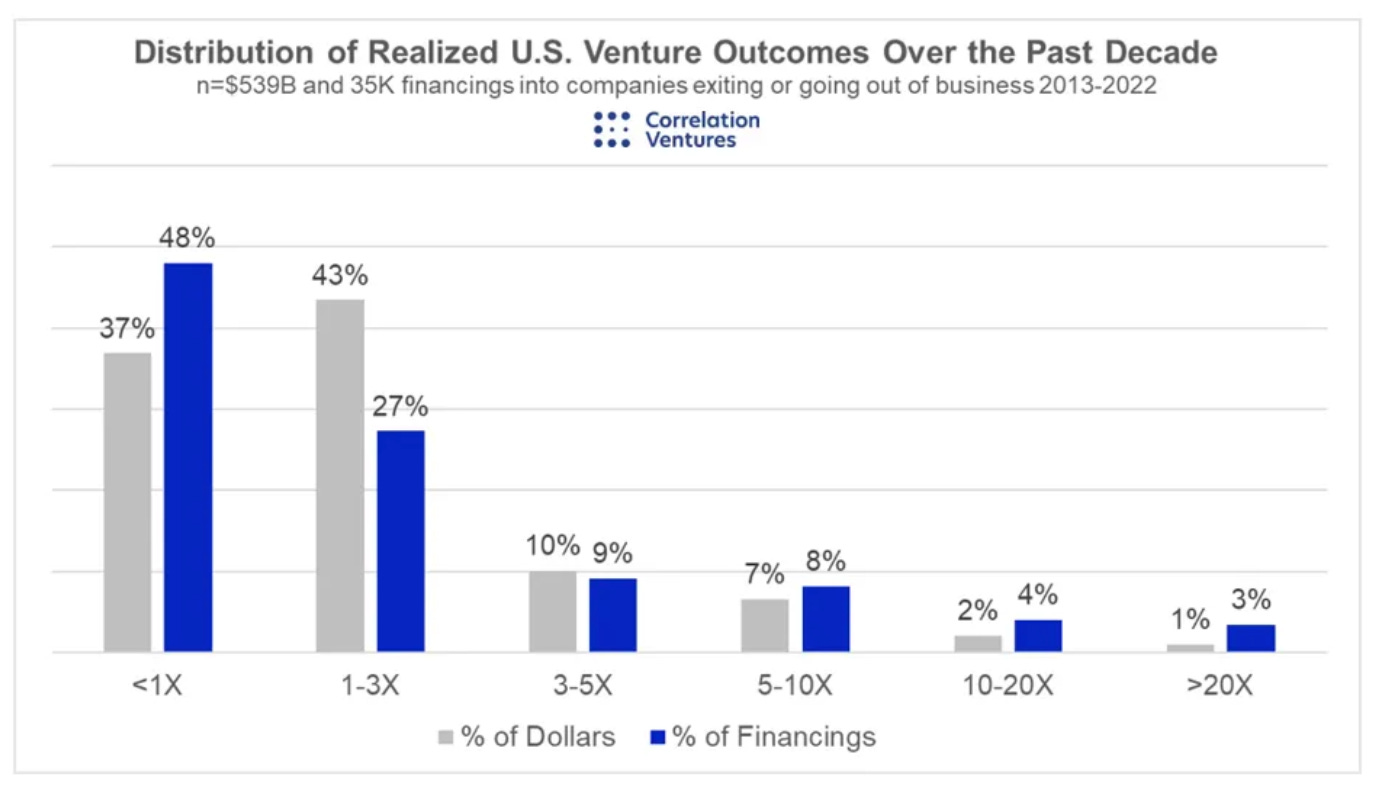

David Corts, General Partner at Correlation Ventures, introduces some fascinating data about US venture capital (see the graph below).

In the graph above, “Financings” appears to refer to investment rounds (or investment deals), while “Dollars” indicates the amount of capital returned from these investments.

Among the startup investment deals that exited over the past 10 years (2013–2022), less than 7% generated returns of 10 times or more, and 48% yielded returns of less than 1× (i.e., resulted in losses). In other words, half of the deals did not turn a profit.

Since details for the “1–3×” range are not provided, the distribution within that range is unknown; however, let’s assume that the average multiple is 2×.

The typical lifespan of a US VC fund is 10 years, although it can be extended by two years with the consent of the LPs. In other words, the fund can operate for a maximum of 12 years.

Currently, the US interest rate is approximately 5%. Suppose you deposit US$100,000 in a bank for 12 years. At a compound interest rate of 5%, that amount would grow to roughly US$170,000. Incidentally, the initial deposit would double in about 14 years at this rate.

On the other hand, if you invest US$100,000 in a US VC, there is a 50% chance of losing money.

The graph below compares investment deals that yield less than 1× with those that produce returns of 10× or more.

Returning to Keith's SignalRank, if you invest in their INDEX, you can expect a higher rate of return than investing in a regular venture capital fund. If I had the money, I'd invest too!

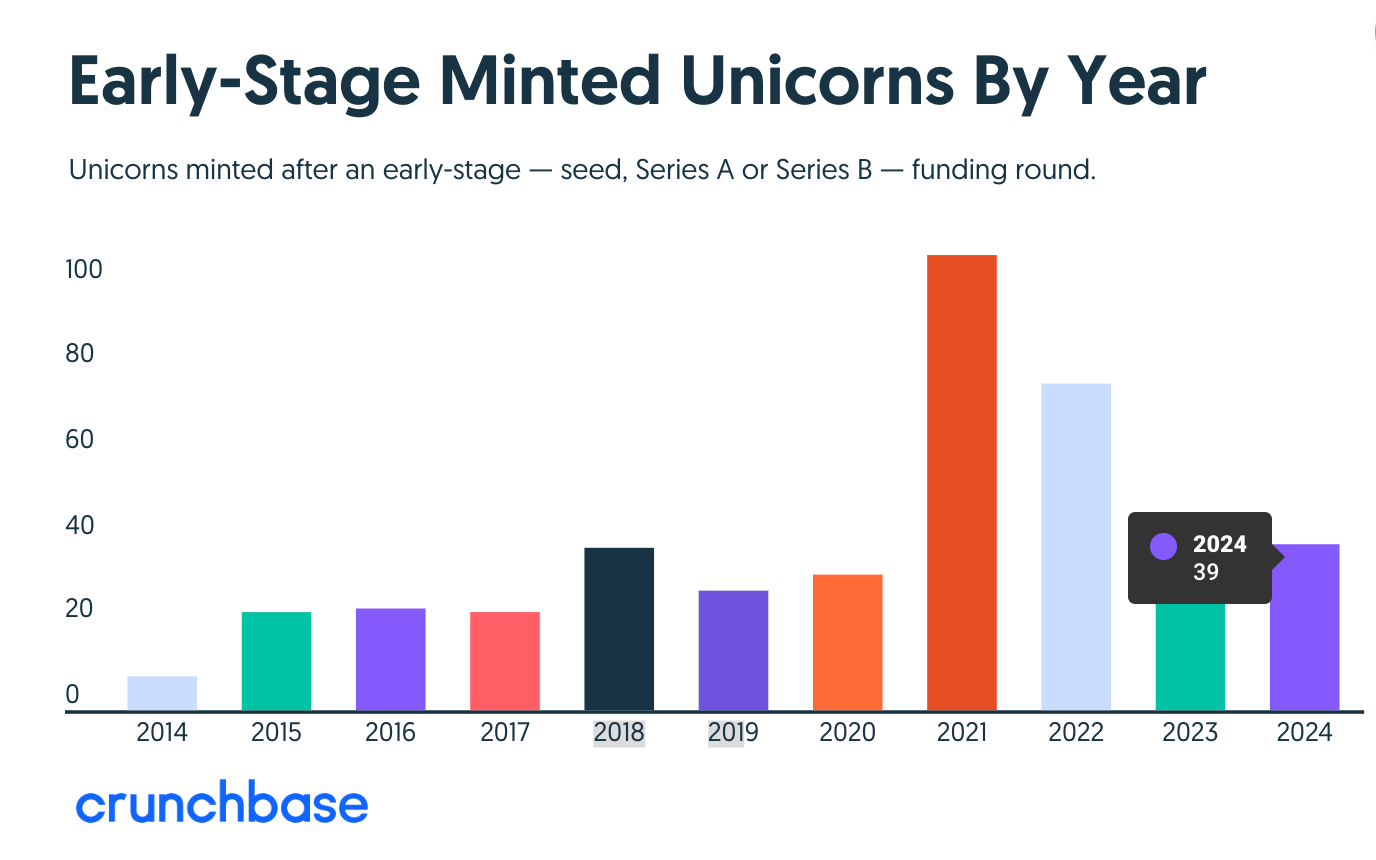

According to data from crunchbase, an increasing number of startups have become “unicorns” at the seed to Series A and B stages. This is probably because AI has made it possible to grow businesses more quickly with fewer people.

AI is definitely changing the world. I, too, will consider seriously how I should use AI in my work.